A Machine Architecture

The GEOS operating system is state-of-the art technology based on the Intel 80x86 microprocessor. This chapter discusses some of the elements of the 80x86 design and history.

Those unfamiliar with the 8086 architecture would do well not only to read this overview but also to pick up a book about the Intel chip series. There are dozens of good books about the 80x86 chips, and this section provides only a brief review.

A.1 History of the 80x86

The commercial microcomputer essentially began with Intel’s introduction of the 8008 chip in 1972. This was an 8-bit machine that eventually led to the 8080 (in 1974), which was the precursor to the processors that now provide the power of today’s PCs.

The 8080 was an 8-bit processor that used seven general-purpose registers and an external 8-bit bus. It addressed 64K of memory; such a small memory space necessitated optimization of each instruction in an attempt to keep as many instructions as possible under one byte in length. This optimization resulted in many instructions being forced to work on specific registers; for example, most arithmetic and logical operations used the accumulator as the destination register.

In 1978, the 8086 followed, bringing 16-bit architecture to microcomputers. The designers of this new chip, however, wanted to aid in quick software development, so they gave the 8086 an instruction set and architecture reminiscent of the 8080-this allowed software based on the earlier chip to be ported to the new hardware quickly and cheaply. The 8086 offered significant advances, most notably the ability to access up to one megabyte of memory in 64K segments.

A year later, in 1979, the 8088 was introduced. This chip had all the advanced features of the 16-bit 8086 except one: Rather than using a 16-bit external data bus, the 8088 used the same 8-bit bus used in the 8080. This step backwards made it possible for systems and peripherals designed for use with the 8080 to be used with a faster, more powerful chip. The 8088 was built into IBM’s personal computers for just this reason.

Both the 8088 and the 8086 can run the same software; they use the same instruction set. However, the power of the data processing offered by the 8086 eventually won out as systems and software became more complex.

A.2 8086 Architecture Overview

The 8086 uses a 16-bit architecture but can handle 8-bit data as well. It accesses up to one megabyte (1024K) of memory, sixteen times more than the 8-bit 8080 could. It has thirteen registers (each 16 bits) plus a status register containing nine flags.

A.2.1 Memory

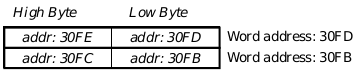

The memory of the 8086 begins at hexadecimal address 0x00000 and continues (each increment representing one byte) to hexadecimal address 0xFFFFF. Any two consecutive bytes constitute a word. The address of a word is the same as the address of its low byte (see Figure A-1).

Figure A-1 Structure of a Word

A word consists of two bytes, the high byte having the higher address.

Both the 8088 and 8086 have instructions that access and manipulate words, and both have instructions that access and manipulate bytes. The 8088, however, always fetches a single byte from memory due to its 8-bit bus. The 8086 always fetches two bytes, or a word; if the instruction only operates on a byte, the excess 8 bits will be ignored. This information may be useful to assembly programmers who wish to optimize the performance of their code, but C programmers can ignore it.

As stated earlier, the 8086 can access up to one megabyte of memory. This translates to 220 bytes, or 220 addresses. However, because the 8086 is designed to do 16-bit arithmetic, it can not directly access all that memory. Instead, an additional mechanism, known as segmentation, is employed.

A segment is a contiguous set of bytes no larger than 64K (216 bytes). It must begin on a paragraph boundary (a paragraph is a contiguous block of 16 bytes, the first of which has an address divisible by 16-that is, its address must have zeros for its four least significant bits). This allows the processor to use just 16 bits (leaving off the four zero bits) to access the first byte of a given segment.

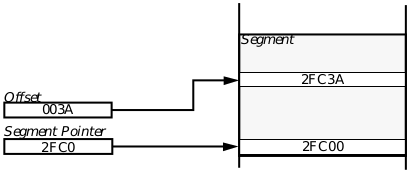

To access bytes further into a segment, instructions use not only the 16-bit segment pointer but also a 16-bit offset. Combined, the segment pointer and offset can specify any byte in memory. (See Figure A-2 for an illustration of accessing a segment.)

Figure A-2 Accessing a Byte in a Segment

Each byte is accessed via a segment pointer and an offset. Note that all addresses shown are in hexadecimal.

Segments may be any size up to 64K. There is no way to specify the exact size of a segment; the processor does not police memory access. Segments may obviously overlap; it is possible, for example, to have two different segments begin 16 bytes apart. Since segments can be any size up to 64K, the two in this example may well overlap.

The addressing mode described above is used in the 8088 and 8086, a large portion of the GEOS market. However, later processors such as the 80386 also employ a protected mode of memory access, in which each process running is relegated a given portion of memory and memory access is policed by the processor. These later processors also can use the segmented mode of the 8086; however, because GEOS applications should be able to run on an 8086 or 8088 machine, they should adhere to the 8086 rules.

A.2.2 Registers

The Intel 80x86 processors have thirteen registers plus one register containing machine status flags. The thirteen registers are separated into four logical groups by their use (they are all 16 bits):

Instruction Pointer

This single register maintains the address of the current instruction being executed. This is not accessed by applications.Segment Registers

These four registers contain segment pointers.Index and Pointer Registers

These four registers contain offsets into segments.General registers

These four registers can contain any general data. They may be operated on as words or bytes.

The Segment and Index registers are used in conjunction to access memory. A program may have four segments pointed to at once: A code segment (CS), a data segment (DS), a stack segment (SS), and an extra segment (ES). These segments have various uses and purposes described in most 8088/8086 books.

The four Index registers are used as offsets into the segments pointed to in the Segment registers. They are the Stack Pointer (SP), the Base Pointer (BP), the Source Index (SI), and the Destination Index (DI). Each of these index registers has special applications with certain instructions.

The General registers are four 16-bit registers that may be used for any purpose. However, due to the early restrictions of the 8080 that carried over into the later processors, some instructions place their results or take their source data from specific registers.

All four general registers may be accessed as a word or as two separate bytes. The four registers are AX (the accumulator), BX (the base register), CX (the counter), and DX (the data register). The high byte of any of these may be accessed by substituting “H” for “X,” and the low byte may be accessed by substituting “L” for “X.” (The “H” stands for “high” and the “L” for “low.”) Figure A-3 shows a diagram of these four registers.

Figure A-3 The Four General Registers

The four general registers of the 8088 and 8086 can be accessed either as entire words or as separate bytes.

A.2.3 The Prefetch Queue

Programmers who code in assembly language should be familiar with how the 8086 fetches data and instructions from memory. Good programmers can take advantage of the more efficient instructions to cut down on processor time for given operations.

The 8086 takes four clock cycles to fetch a single word from memory. To speed up instruction processing, the 8086 has a prefetch queue, a buffer of six bytes into which pending instructions are put. The 8086 is also broken into two separate processing units: The Execution Unit executes instructions while the Bus Interface Unit (BIU) fetches pending instructions and stuffs them into the prefetch queue.

The main goal of this separation is to make as much use of the bus as possible, even when an instruction that does not access memory is being executed. For example, if an instruction takes eight cycles to execute and does not access memory, the BIU could meanwhile fill four instructions into the prefetch queue. Therefore, while slow instructions are still slow, the instructions after them appear to be quicker.

However, jump and branch instructions negate this prefetch effect. When a branch or jump is executed, the prefetch queue is flushed and must again be filled.

A.2.4 Inherent Optimizations

The 8088 and 8086 instruction set was designed with many instructions manifested in two different forms: one that allowed a wide range of possible arguments, and another that worked with one of the arguments prespecified. Since the second form did not have to load both arguments from memory, those instructions were shorter than their counterparts.

For example, the instruction and has these two forms: “And with anything,” which assembles into three bytes of machine code, and “And with AX or AL,” which assembles into only two bytes of machine code. Thus, the instruction and al, ffh is more efficient than and bl, ffh.

Another optimization occurs in the set of string instructions. A string is simply a set of consecutive bytes or words in memory. To repeat an operation on each element of the string could normally take a long time due to branching and checking for final conditions (branching clears out the prefetch queue). However, the string operations act as single, nonbranching instructions, so the prefetch queue is not affected by them. This speeds up string operations considerably.

Drawing Graphics <– table of contents –> Threads and Semaphores